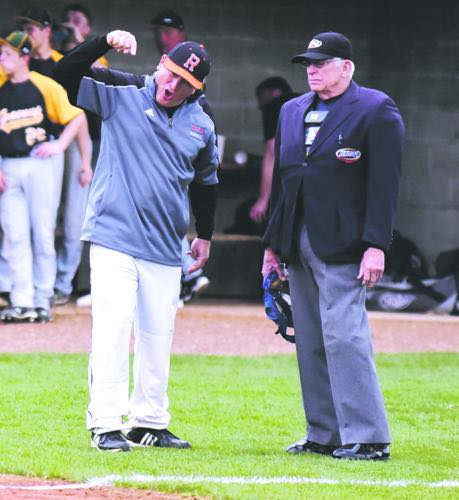

LEXINGTON, Ky. – Jody Hamilton, whose remarkable 41-year high school baseball coaching career includes 1,038 victories, two state championships and National Coach of the Year recognition, is part of the Dawahares’ Kentucky High Schol Athletic Association 2026 Hall of Fame class.

Hamilton, a 1976 graduate of Ashland, won state championships at Boyd County in 2001 and West Jessamine in 2015. He also captured the All-A State title in 2024 at Owensboro Catholic and was the All-A runnerup at that school in 2025.

Hamilton was at Boyd County and West Jessamine for 16 years apiece and at Raceland for four years. This spring will be his fifth season at Owensboro Catholic,

He became only the fifth coach in Kentucky history to reach 1,000 victories, crossing that milestone in 2024. He is the only coach with state championships at two different schools.

The top four coaches on the Kentucky win list accomplished their 1,000-plus victories while coaching at the same school. All-time wins leader Mac Whitaker is still coaching at Harrison County and Bill Krumplebeck of Covington Catholic retired after last season.

Taking his place in the KHSAA Hall of Fame is an honor that is well deserved for one of the best high school baseball coaches in Kentucky history. He has helped countless players – his own and rivals alike – to college scholarships and was largely responsible for elevating baseball programs through the 16th Region during a dominating run there from 1987 to 2002.

Programs were forced to improve facilities and skills to try and keep pace with the Lions who were also state runnerups twice under Hamilton.

Hamilton, who is still the head coach at Owensboro Catholic, was the 2016 National High School Coaches Association Coach of the Year. He was a charter member in the Kentucky High School Coaches Hall of Fame, the 2016 NHSCA Coach of the Year and the Kentucky High School Baseball Coaches Association Coach of the Year in 2001 and 2015.

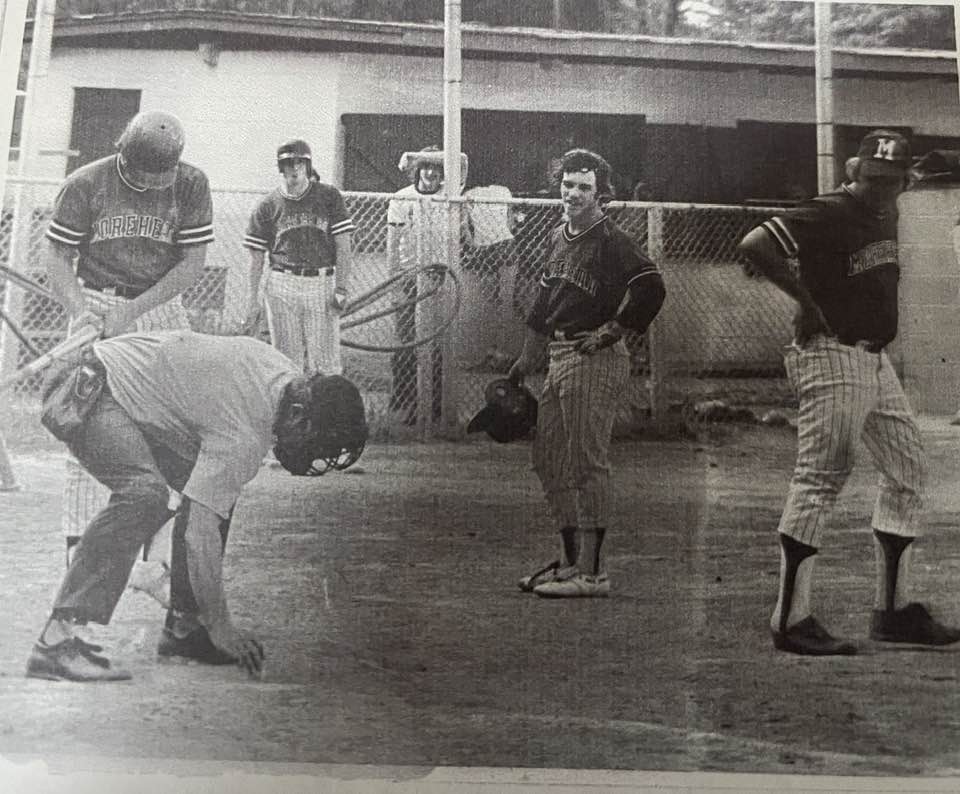

He was also a charter member of the Ashland Baseball CP-1 Hall of Fame in 2015 and is a member of the Morehead State Athletic Hall of Fame after an illustrious playing career that included being named Ohio Valley Conference Player of the Year after winning the league Triple Crown in 1977. His 49 career home run record stood until being eclipsed in 2024.

Jody played one year professionally for the Paintsville Yankees, including debuting the same night that Darryl Strawberry did for the Kingsport Mets.

Despite a successful first season in pro ball where he hit better than .300 with the prospects of moving up in the Yankee organization, he decided to embark on a coaching career that has been full of highlights. His career began as the head coach at Raceland High School in 1983. He later moved to Boyd County, then West Jessamine and is currently at Owensboro Catholic.

Hamilton coached golf from 2007-2010 where his teams were four-year regional champions and finished third at state in 2010 and seventh in 2009 at West Jessamine. He served as an assistant football coach at Raceland and West Jessamine in a career defined by success.

He endured only one losing season in his career, going 15-17 in his last year at Raceland in 1986 when every game was played on the road. Raceland won the district crown in ’86, anyway, and was the home team on the scoreboard for the first time — in 28 total games — in the opening round of the 16th Region Tournament.

Hamilton moved to Boyd County and captured his first of 11 region championship trophies with the Lions in 1988, taking them to the state championship game. Casey Hamilton, Jody’s son, helped bring Boyd County to a state title in 2001. He started at West Jessamine in 2004 and the Colts collected four region crowns (2008, ’10, ’15, ’16) under his leadership. He has two regional titles at Owensboro Catholic.

Winning the state championship and getting attention from college recruiters for his players was always the goal for Hamilton, who estimated 70 percent of the seniors who played for him found themselves on college rosters.

The secret sauce for Hamilton’s teams have been pitching and defense. All but “one or maybe two” of his starting catchers throughout his 41 seasons have gone on to play college baseball. Two of his pitchers at Boyd County, Jason Keyser and Casey Davis, were drafted in the eighth and ninth rounds, respectively. He has helped more than 125 players find a place to play in college.

Hamilton operated a baseball school while coaching at Boyd County and one of the pupils was Brandon Webb, a future Cy Young Award winner for the Arizona Diamondbacks. Webb was 10 when his father, Phil, took him to Hamilton. He worked with him for five years before telling him he had to stop because Webb would soon be pitching for Ashland, Boyd County’s biggest rival.

“I said, ‘Brandon, here’s what’s going to happen. I have to stop giving you lessons because, if I keep giving you lessons, you’re going to beat me. People aren’t going to like that. If I don’t keep giving you lessons, I’m going to recruit you, and then I’m going to get fired.’”

In an unusual twist, Webb never faced Boyd County as a Tomcat. Coaches held their top pitchers during the regular season for a potential district matchup. Ashland and Boyd County never drew in the first round through his junior year. Webb’s senior season was cut short by an injury.

“How many coaches can say they gave lessons to a Cy Young winner?” Hamilton asked.

Jody and wife, Denise, have two grown children and several grandchildren and live on a farm in the Owensboro area.