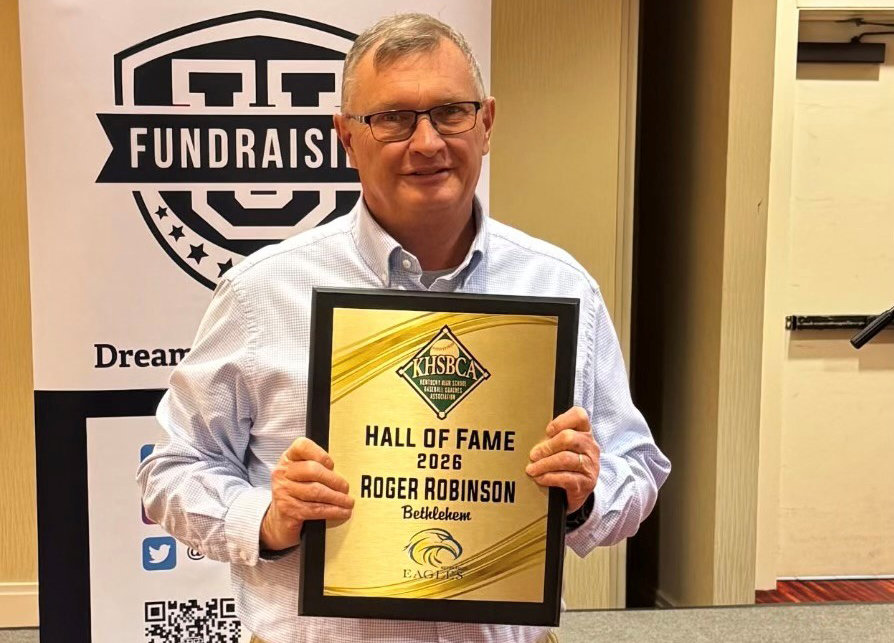

An Ashland native who cut his baseball teeth in his hometown was elected to the Kentucky Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame on Friday night.

Roger Robinson, a 1984 graduate of Ashland where he played for Frank Sloan, was recognized for building the Bethlehem baseball program for nearly 20 seasons. He has accumulated 327 victories despite being the smallest school in the Fifth Region. That’s an average of 20 wins per season in a program that, before his arrival, had only one district tournament victory.

He has changed the attitude and expectations for Bethlehem since taking over in 2007. That’s 18 seasons in 19 years with the COVID year included when no games were played. He starts season No. 20 in the spring.

Bethlehem, a private school, has a boy-girl enrollment of about 300 so his pool of players to choose from is around 150. Compare that with Central Hardin Elizabethtown and Taylor County who have enrollment in the thousands, and it has been an uphill battle, Robinson said.

However, he guided them to the regional championship game in 2013, falling to perennial power Elizabethtown 2-1. He was named Fifth Region Coach of the Year that season.

“That’s as close as we’ve been to winning the region but historically, we go to the region (since his arrival) every year,” said Robinson, who also credited longtime assistant Billy Lyons with the program’s success.

Robinson’s baseball knowledge comes through some good genes. His father, also named Roger Robinson, was a highly successful youth league baseball coach in Ashland for many years. He coached in Little League (major and minor), Babe Ruth and Senior Babe Ruth. The elder Robinson was on the ground floor of getting Babe Ruth baseball started in Ashland in the 1950s.

Roger played for his father throughout his youth career and said the experience was a great one.

“A couple of stories I can think about dad and baseball and the differences of then and now, back when he was coach, they got the practice field on first-come, first-serve basis,” he said. “He’d work the midnight shift at Armco, get off work at 6 a.m. and take the bat bag and put it on the diamond. We’d have early-morning practices.”

It was a baseball family for the Robinsons. Roger’s late mother, Margie, learned to keep the scorebook for her husband and his little sister, Jill, learned how to spend her free time at the ballpark, too.

When Roger Sr. was coaching Armco in the Senior Babe Ruth, Roger Dean was a batboy from 4 years old to 8, taking in the experience of being at the ballfield and around some elite Ashland players. Five decades later, the love of the game has not faded and he’s still on the ballfield.

He has translated that into a successful high school coaching career at Bethlehem. As a professional, he was a physical therapist until he retired. Now he helps with medical assistance for high school teams.

His wife, Cindy, attended private schools and they enrolled their four children at Bethlehem. Roger watched the team play when his boys were young and it wasn’t always pretty. He became an assistant coach and a year later was promoted to the head coach and the rest is history, including have both of his son play for him – like father, like son.

They have won the All “A” regional tournament four times.

“It was a start-from-nothing kind of process,” he said. “A lot of fundraising, an indoor facility and a much nicer field than they used to have made a difference. One of the things I’m most proud of is that we have a full varsity, junior varsity and freshmen teams. To have teams on all three levels for a school our size is tremendous.”

Robinson started the Bethlehem Prep Baseball Program that develops players from K-8th grade for students attending a Bethlehem feeder school.

In his speech on Friday, Robinson said it’s not all about wins and losses at Bethlehem.

“The biggest reason I got into coaching, and one of the things that drives me, and the person I thank most is our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ,” he said. “I’m trying to represent the Lord when I’m out on that field. It’s what we try to do every time we play at Bethlehem. That is the reason I continue to coach.”

Hearing some of the other speeches about their playing days, Robinson said he once pitched a no-hitter as an 8-year-old on the Foodland Rockets that drew some laughs.

“What I didn’t tell them was I walked 17 and gave up 15 runs,” he said.

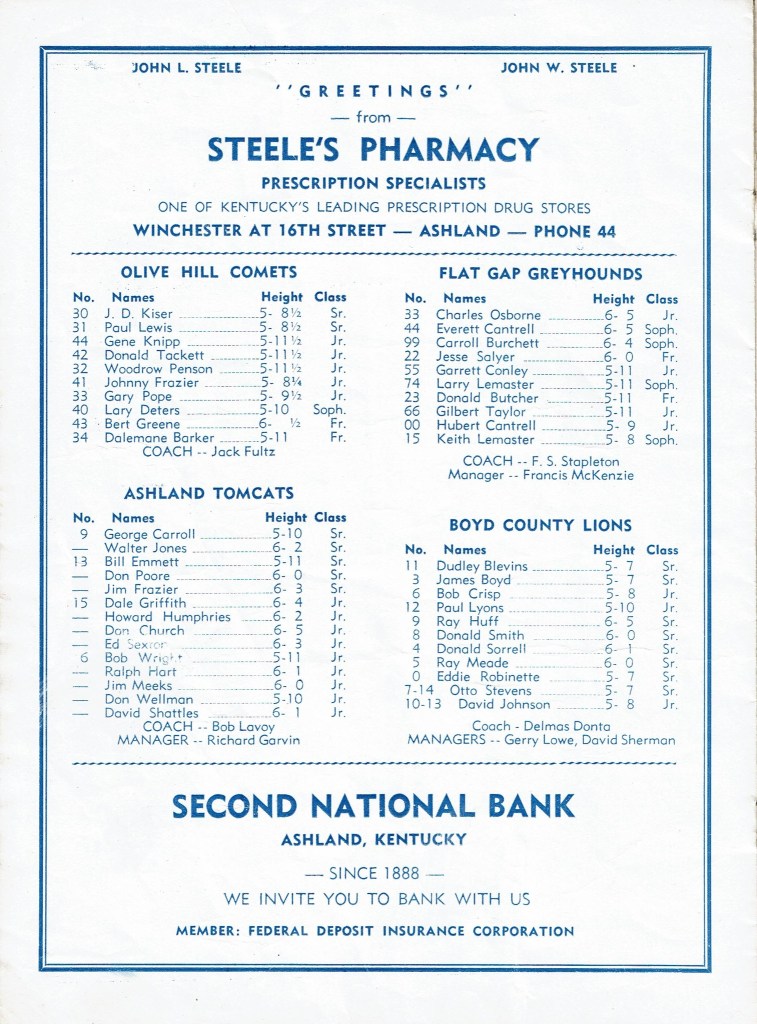

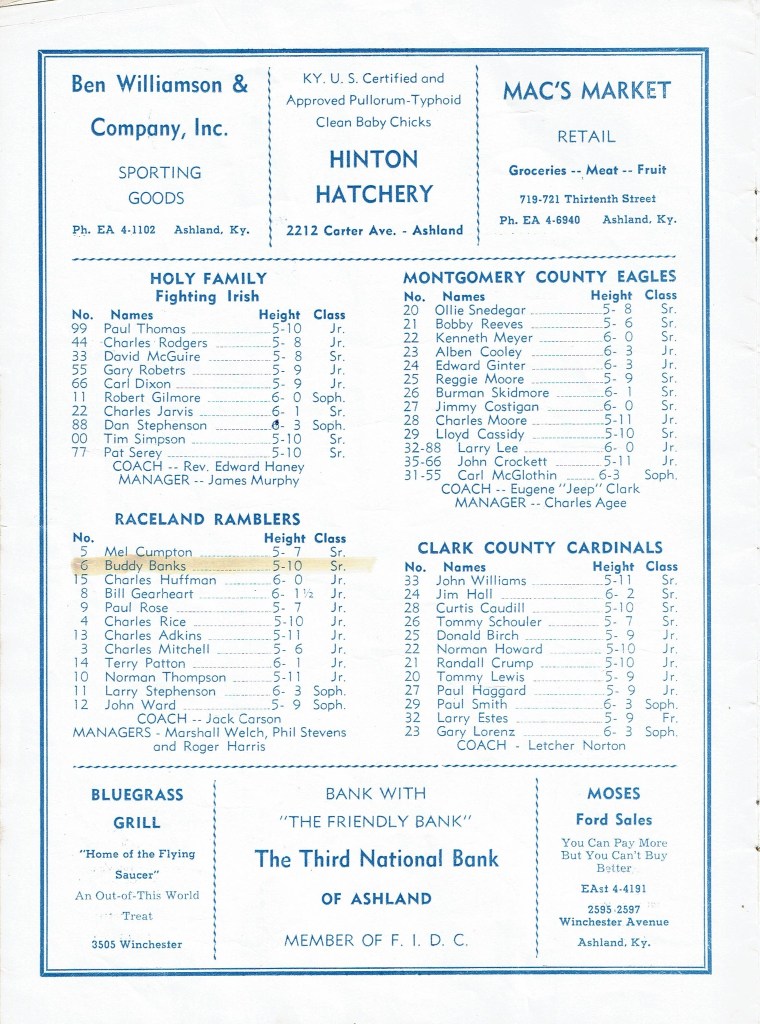

Roger played for the White Sox in Ashland American, the Eagles in Babe Ruth, the Tomcats in high school and for Post 76 under Frank Wagner and Paul Reeves.

Robinson thanked his father, his coach throughout his youth baseball days, for instilling in him a love for the game.

“He certainly doesn’t agree with all my philosophies, but that’s OK, he will learn,” Robinson said.

He also thanked his wife for putting up with him and always being supportive. Besides the four grown children, he also has seven grandboys so that means more coaching in his future.

“I had them in the (batting) cage yesterday,” he said.