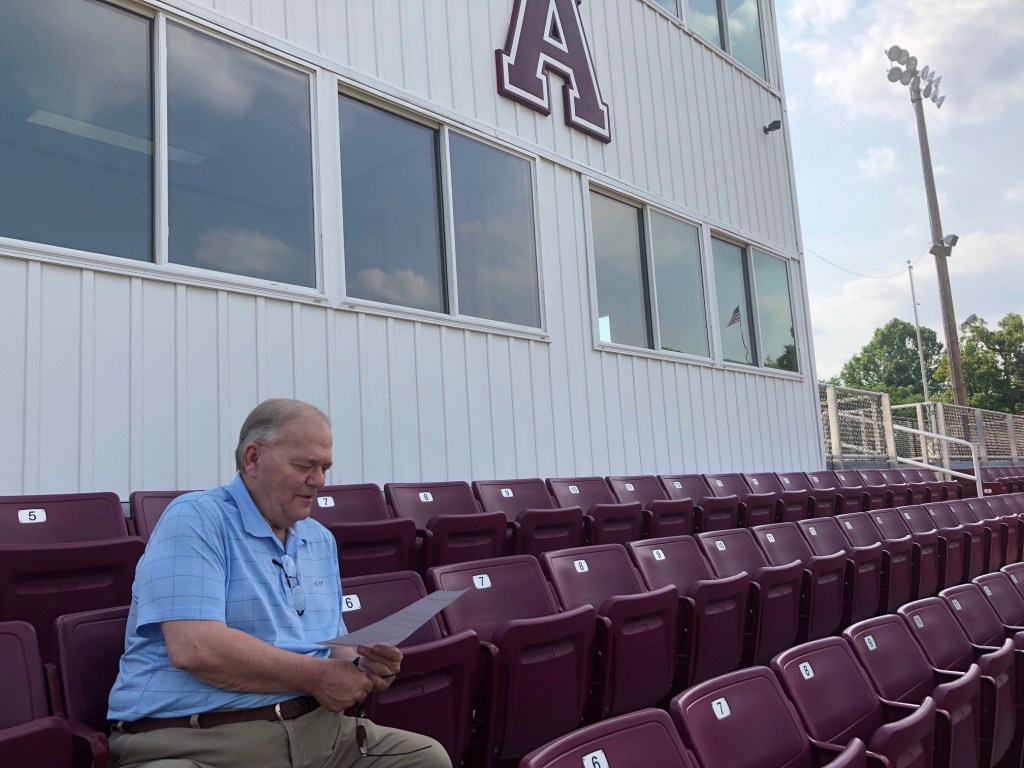

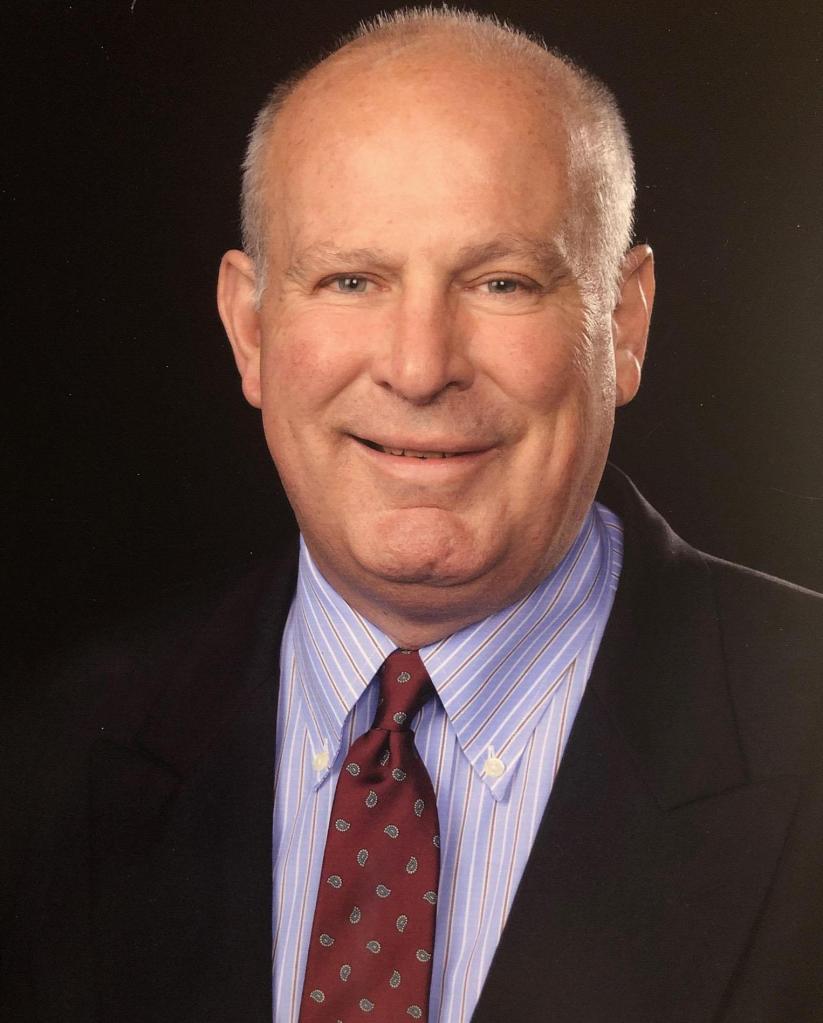

Steve Dodd, a former Ashland Tomcat basketball standout and a respected high school and college coach, passed away Monday from injuries sustained in an automobile accident last month. He was 70.

Dodd starred for the Tomcats from 1971–73, serving as a key reserve on the 1972 team that was ranked No. 1 in the state but was upset by Russell, 80–75, in the 16th Region championship. Fittingly, 34 years later in 2006, Dodd guided Russell to its first regional title since that very season.

During his six years as the Red Devils’ head coach from 2002–08, Dodd compiled a 98–84 record and reached at least the 16th Region semifinals in five of those seasons before resigning.

A 1973 Ashland graduate, Dodd went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in English from Lipscomb University, where he was also a standout player. It’s also where he met Kay, his wife of 48 years. They had a son and daughter.

Soon after graduating, he began his coaching journey as an assistant at Battleground Academy in Franklin, Tenn.—the start of a nearly 50-year coaching career. Dodd’s coaching stops included Alderson Broaddus University, Oklahoma Christian University, Bethel College, and Lindsey Wilson College, where he led the program from 1998–2002 and enjoyed great success. His contributions to the sport earned him induction into the NAIA Hall of Fame.

After his time at Russell, Dodd took over at Hillwood High School in Nashville, leading the Hilltoppers from 2008–19, and most recently coached at Dickson County High School in Dickson, Tenn.

Dodd’s passion for the game went far beyond wins and losses. He was known for shaping young men both on and off the court—a fact reflected in the many heartfelt tributes shared by former players and colleagues Tuesday.

Todd Parsley, who served as Dodd’s assistant coach at Russell, told sportswriter William Adams of the Ashland Daily Independent that coaching alongside him was a privilege.

“I don’t think people knew how much he cared about his players,” Parsley said. “He had kids that would run through walls for him because I just saw the personal side of coach. When kids were having trouble with their home life, he was there helping them. He was far greater than just wins and losses.”

Dodd’s brother, Gary, said coaching was Steve’s lifelong calling.

“He had 11 fractured ribs, four fractured vertebrae, and a bad concussion, but when he heard that, it was like, ‘I can pursue this, I can do that,’” Gary said. “He wanted to get back out there at age 70 and have another shot at trying to do that, even for the interim.”

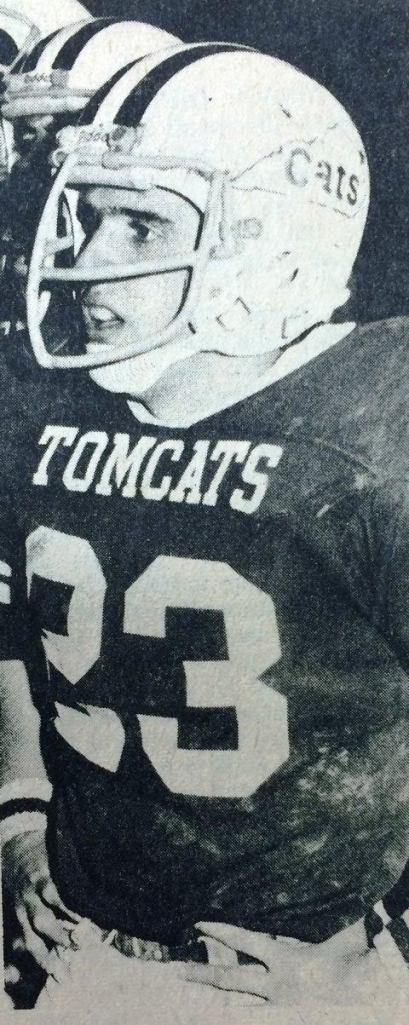

As a player, Dodd was known for his toughness and scoring ability, averaging 15.8 points per game as a senior. That year, Ashland fell to Boyd County twice—first in the 64th District finals, 77–73, and again in the regional championship, 73–64, despite Dodd’s 21- and 22-point efforts. It was the first time Boyd County had beaten Ashland in basketball.

Dodd finished his Tomcat career with 669 points, including a career-high 27 against Fairview.

From his days wearing Ashland’s maroon and white to his decades molding athletes across the country, Steve Dodd left a lasting mark on basketball—and on everyone he coached.