The sound coming from the radio was more static than voice — unrecognizable, unfamiliar. It wasn’t what it should have been.

Driving home to northern Kentucky after watching the first quarter of Ashland’s game with Rowan County two weeks ago — on the night the famous JAWS team was being honored — I searched the dial for the Tomcats’ broadcast and finally landed on it.

Or did I?

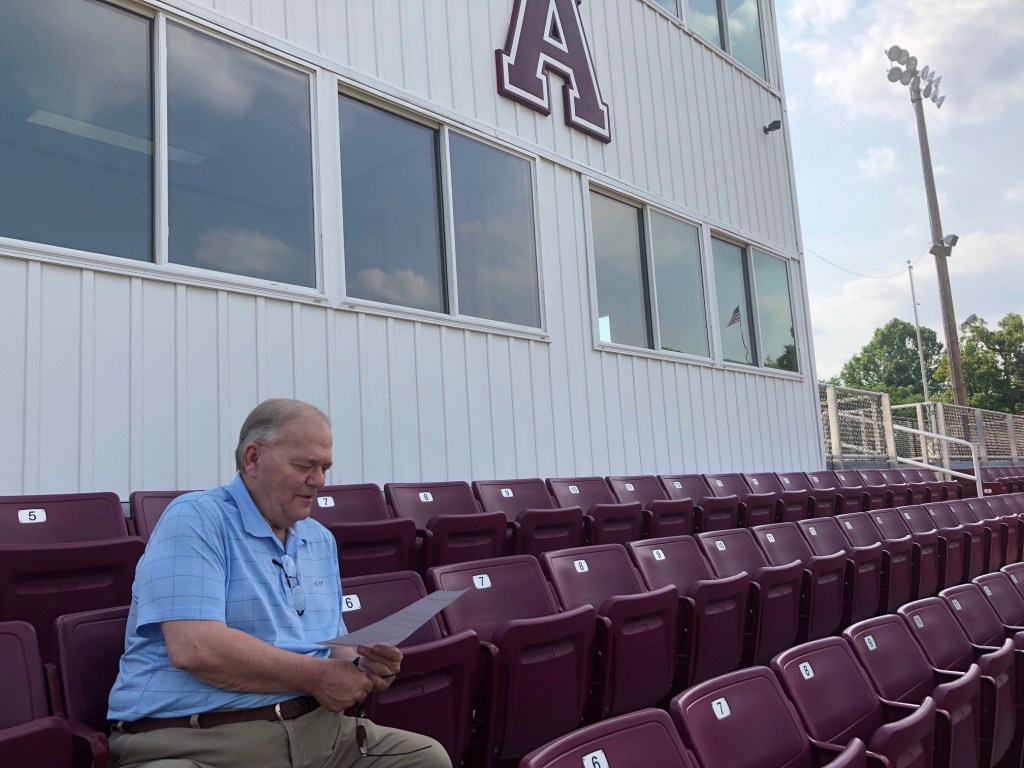

The announcers were doing a fine job, especially considering Ashland was up 48-0 by halftime. But it wasn’t the same. Because it wasn’t Dicky Martin — the unmistakable voice of the Tomcats — calling the game from the Putnam Stadium press box that bears his and his father’s name.

Dicky wasn’t there because he was in the hospital, locked in the fight of his life — a fight he sadly lost to cancer Wednesday night. Even knowing he wouldn’t be on the air, instinctively turning the dial to find him felt like something that should still work. For half a century, it always had. Entering his 50th season as Ashland’s play-by-play man, he had missed only two games.

I tried to listen. My mind wouldn’t let me. I turned it off.

Ashland is a place steeped in tradition, and Dicky Martin was part of that tradition’s fabric. The Martin family — Dicky and his father, Dick — gave Ashland 73 years of Tomcat broadcasts between them. People like to say no one is irreplaceable. But when it comes to Ashland Tomcat sports, Dicky Martin proved that saying wrong.

Born with a silver microphone

Some people are born with a silver spoon. Dicky was born with a silver microphone.

His father, Dick Martin, moved the family from Huntington to Ashland in 1952 and started broadcasting Tomcat games on WCMI the next year. He was a sharp businessman who understood that community radio needed sports — and that Ashland needed its voice.

Both Martins had a similar style: blunt, passionate, fiercely loyal. They never hesitated to call out poor play or questionable officiating — all through maroon-tinted glasses. Dicky often said, “There’s an on-and-off switch on your radio if you don’t like what you hear.”

He could be hard on the Tomcats, but no one else better be. Criticize his team, and you were taking on family.

Dick Martin became as much an icon as his son would later be. He even served as Ashland’s mayor, but it was his radio work — and his love for the Tomcats — that defined him.

Dicky once laughed recalling a moment from his childhood when his dad waved a handkerchief at a referee. “The ref came over and said, ‘You got something to say?’ Dad said, ‘Here, talk right into the microphone.’”

The referee rolled his eyes and went back to the game. Soon enough, the calls evened out.

That was Dick Martin — unfiltered, bold, and impossible to ignore.

Learning the craft

Dicky learned early that preparation mattered. His parents made him listen to recordings of his voice and work on his diction. “I had that Ashland twang,” he told me once. “They made me pronounce and enunciate until I got it right.”

Few were ever more prepared behind a mic than Dicky Martin. He could deliver a sharp one-liner at just the right moment — often unrehearsed, sometimes regretted, but always memorable.

“It’s humbling,” he said, “that people bring radios to the games just to listen.”

In his early days, his passion sometimes got him in trouble. He was banned once from the Boyd County Middle School gym. Some Tomcat fans didn’t always agree with his takes, but they still listened — often through headsets in the stands, wanting his voice to accompany what they were seeing.

His first broadcast came in 1973 when his father pretended to lose his voice and handed the mic to Dicky during a Raceland–Holy Family game. Dicky had just graduated from Ashland the year before. By 1975, he was the full-time voice of the Tomcats.

The rest, as they say, was history.

A voice shaped by legends

Dicky often said he learned from three of the best: his father, UK legend Cawood Ledford, and Hall of Fame broadcaster Marty Brennaman. “My dad was the best,” he said. “I learned from him, from Cawood, and I love to listen to Marty. He’s the best one living.”

Patterned after greats, yes — but Dicky was one of a kind.

“I’ve mellowed a lot,” he told me a few years ago. “I’m kind of like a fan in a way. When a guy misses a call, the fans go, ‘Oooooooh!’ I just get to do it over the air.”

The “Three D’s” and lasting friendships

This story isn’t complete without mentioning his longtime sidekick, David “Dirk” Payne, who passed away a few years ago. Dicky loved him deeply. “There aren’t many men I love more than him,” he said. “When my dad died, Dirk thought it was me. He had a stroke that day. One day I lost my father and damn near lost Dirk, too.”

Dirk and Dicky on the air were Ashland’s equivalent to Marty and Joe with the Reds. You never wanted to miss a second.

Longtime fan Donna Suttle was another dear friend. She called them the “Three D’s” — Dicky, Dirk and Donna. Her heart is broken now that trio is down to one.

He had many more friends in Ashland. Everybody knew of Dicky Martin and his love for the Tomcats.

Beyond the Tomcats

Dicky’s voice wasn’t confined to Ashland. His career took him to Soldier Field, the Gator Bowl, Ohio State’s “Shoe,” and RFK Stadium while calling games for the semipro West Virginia Rockets. He worked Morehead State basketball games during Wayne Martin’s coaching era, which took him to Madison Square Garden and two NCAA tournaments.

But his heart was always at home.

“My two favorite places are Putnam Stadium and Anderson Gym,” he said. “I love those places.”

He had been to every state basketball tournament since 1976 — and his father took him to his first in 1961, when Ashland won it all. He was just seven years old then, but he never forgot.

Football was his true passion. “I never dreamed I’d be doing this as long as I have,” he said. “But I loved every second of it.”

So did we, Dicky.

So did we.