The news that Darryl Smith had died while taking his morning walk on Monday was hard to process. He was a former Ashland Tomcat two-sport standout about the time I was trying to figure out this sportswriting business. I’ve written numerous stories about him through the years when he was an athlete, a coach and a highly successful college basketball referee. I always considered him a friend.

He was an outstanding athlete in baseball and basketball and an even better person. He came from good stock, and one of the best Tomcat families in history. The late John and Rhoda Smith had five sons – David, Doug, Darryl, Daniel and Deron – and the Ashland community benefitted from having this fine family in the area for reasons far beyond sports. People like the Smiths were building blocks of great communities.

Darryl was a crafty left-handed pitcher, and he turned around at the plate and batted righthanded. He was good at both. He also was on back-to-back 16th Region basketball championship teams in coach Paul Patterson’s first two seasons as head coach.

But baseball was where it was for Smith, who went to Cumberland College to pitch.

After college, Smith signed on to coach Mike Tussey’s inaugural Stan Musial team in 1982 and played every summer through 1986 where he was a dominating pitcher and first base with a powerful bat.

He hung up playing for coaching as he became a mentor for baseball players in Boyd County when he coached Catlettsburg Post 224’s Legion team, including winning a state championship in 1988.

For all that, Darryl Smith was an easy choice as one of the 101 people to be inducted into the CP-1 Hall of Fame. He was in the 2019 class. I remember calling him to tell him the news and he was so excited and honored. It was something he never expected and appreciated so much. Darryl would join his younger brother, Daniel, in the CP-1 Hall of Fame.

He was living in Jacksonville, Fla., and I asked him if attending the August ceremony would be a problem and he said, absolutely not, he would be there. Smith came that sunny afternoon and so did his parents. They were so proud of him and the rest of his athletic siblings.

Of course, travel wasn’t a problem for Smith. He was used to that after more than a decade of being a college basketball referee and, naturally, a good one. He rose through those ranks rather quickly and that was no surprise to anyone who knew him.

Jody Hamilton, a former teammate on the Tomcats, called him a great teammate. Jody also had superlatives about the Smith family, which was all about the Tomcats.

“Darryl was much like his dad. Never panicked, calm with strong presence,” Hamilton said.

The entire infield of the 1976 Tomcats baseball team – Smith (pitcher), Herb Wamsley (catcher), Mark Swift (second base), Greg Jackson (third base), Don Allen (shortstop) and Hamilton (first base) – are in the CP-1 Hall of Fame along with their coach, Frank Sloan. They were regional champions.

Teammates like these all raved about the competitiveness and quiet confidence that was a part of Smith’s DNA as an athlete. He was a winner who played the game the right way.

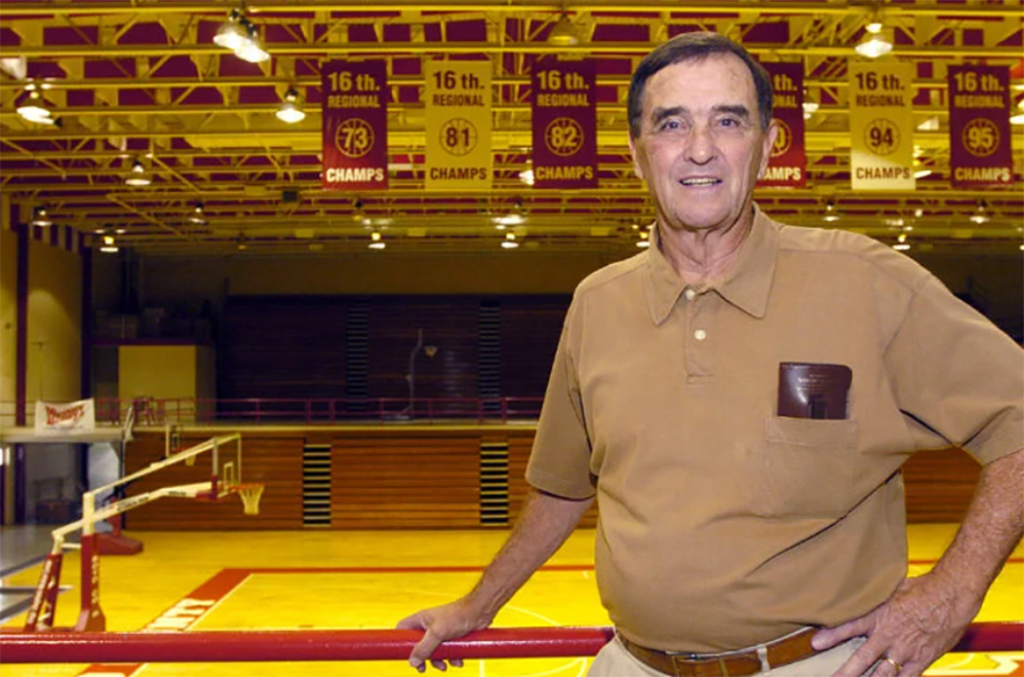

Smith was a role player for Patterson because that’s what everyone did for the coach who never lost a game to a 16th Region opponent in his four seasons. During his senior year, he was surrounded with great talent – Jeff Kovach, Jim Harkins, Mark and Greg Swift, Dale Dummitt, Don Allen and others. That 1977 team went 30-2 and reached the state semifinals before losing to Louisville Valley in Freedom Hall.

Smith had several games in double figures and led the Tomcats twice with 14 against Ironton in a hard-fought win and 18 on Senior Night against Montgomery County. But he was mostly in there for rebounds, screening and defense. That was the Patterson way.

As a college basketball referee, he would often cross paths with players who had ties to the 16th Region. He 2010, he was officiating a game where Paul Patterson was coaching at Taylor University. Scott Gill, a former Russell High star and son Ashland grad David Gill, was playing for Taylor. He posed for a photo with them afterward.

Last Thanksgiving, he met former Tomcat point guard Colin Porter and his mother, Hilary, in the lobby of the hotel where Liberty University was playing. Darryl, who was officiating the tournament Liberty was participating in, was always affable.

Darryl Smith, who graduated from Ashland In 1977, will be remembered for a long time for how he carried himself as an athlete, a coach and in life. His death leaves a void for his family and friends that is hard to fill. He is gone far too soon.