The blockbuster movie “JAWS” came out in the summer of 1975 and frightened viewers who were so traumatized they barely dipped their toes in the ocean.

That summer, Herb Conley took his family to Mrytle Beach, an annual pilgrimage for the family. They would set up at a campground and make daily trips to the beach. The three boys – Greg, Shawn and Jeff – were all under 10 and braver than their mother Janice wanted them to be.

Each day they went a little further into the ocean and Janice told Herb she was not comfortable with how daring the boys were becoming.

Herb had an idea. He remembered there was a movie about sharks that had just come out and he took his young family to the movies to watch “JAWS.” The boys sat wide-eyed through the terrifying movie. Let’s just say Janice did not have to worry about the boys getting too far out into the ocean because they barely got back in the water at all the rest of the trip.

“JAWS” had made an impact on Herb Conley, but it would not be the last one for Ashland’s veteran head football coach.

Living up to the JAWS nickname

He returned to Ashland refreshed and looking forward to the 1975 football season. Conley was anticipating a good season given that it was a strong senior class and some of them would be entering their third year of either starting or playing a lot.

It was a season built for success with a combination of speed, size and power. They were developed very much in the image of their coach – hard-nosed, hard-hitting and determined (afraid?) not to make their coach proud. Herb Conley commanded respect as a player, as an assistant coach and as the head coach. He was in his eighth season as the Tomcats’ head coach and a group that he believed was as good as any since the 1971 and 1972 seasons.

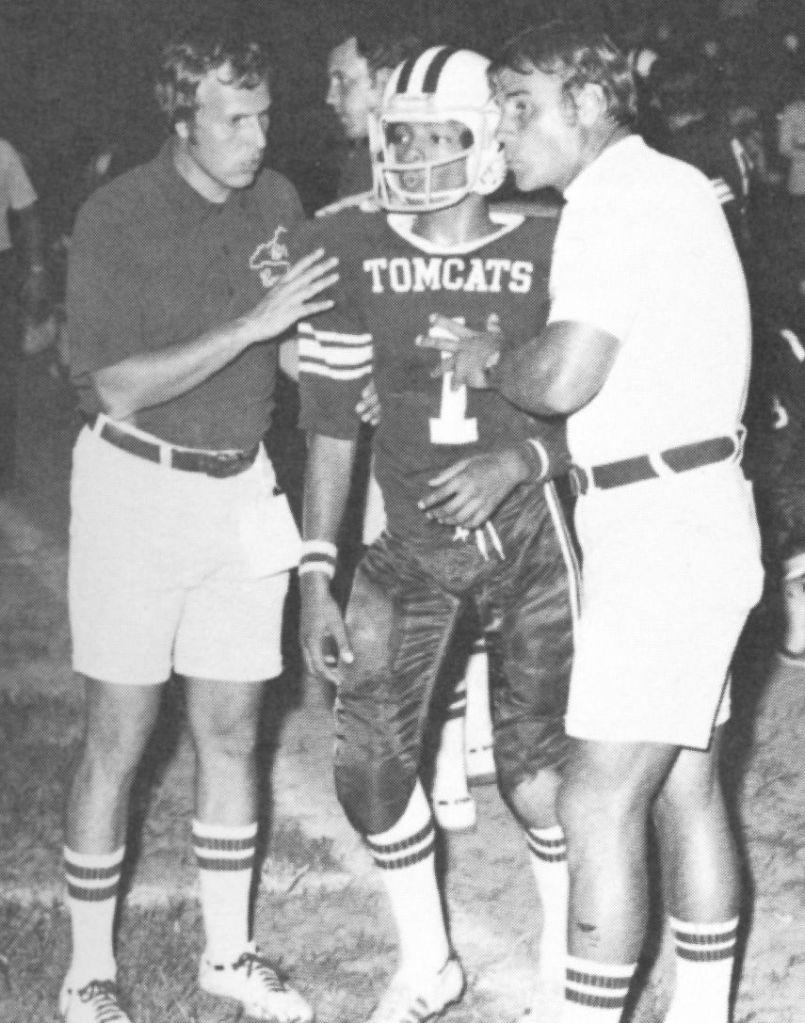

When Conley met with his assistant coaches before the season, he mentioned how his boys were scared to death after watching “JAWS” at the beach. Conley mentioned the possibility of naming the defense “JAWS” mostly as a joke. But coaches Mike Holtzapfel and Bill Tom Ross loved the idea.

Conley was less sure it was a good idea because, as he put it, sometimes those things backfire on you. But Holtzapfel and Ross would not let it go, and Conley told them only if the team could prove it. That is also what they told the players, who were excited about naming the defense after the terrifying shark from the movie.

It took one game for Conley to be convinced that this “JAWS” nickname might be a good thing. The Tomcats blasted Johnson Central 41-14 in the opener at Putnam Stadium and hard-hitting Chuck Anderson knocked the Golden Eagles’ quarterback out of the game with a crunching hit that also knocked the breath out of him.

When Coach Conley went out on the field to check on him, Anderson could barely breathe but he practically begged his coach to let the team be “JAWS.” Conley pulled him up by the belt and helped his biggest hitter off the field. He would return to the game, but Johnson Central’s quarterback would not.

It became clear that it was no longer safe to go on the football field if the “JAWS” defense was the opponent.

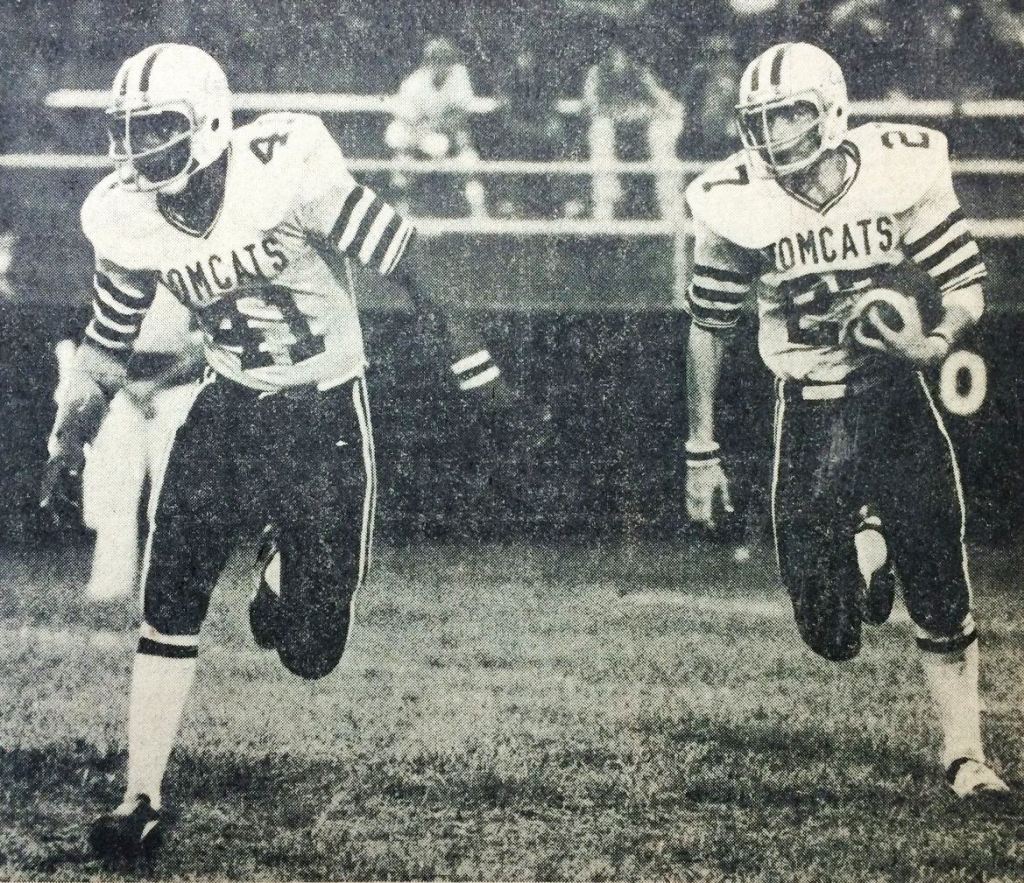

The Tomcats kept it to themselves until after the second week of the season when they defeated top-ranked Bryan Station, 22-12, with another big hit from Anderson spurring a brilliant defensive effort.

He knocked a would-be tackler unconscious with a block that sprung Rick Sang for a touchdown on a punt return that put Ashland ahead 12-0. It also set the tone not only for that game but the season.

Eventually, the media at the time got word about the “JAWS” defense and the Tomcat band even learned the memorable music from the movie when the shark was about to attack. Fans brought plastic sharks to the games and the businesses in town were prompting “JAWS” defense on their signs.

Everybody bought in, especially the team.

Make a wish(bone): A dominating offense

Ashland rattled off win after win during the regular season and went into the playoffs unblemished and ranked No. 1 in Class AAAA – then the biggest classification in the state. They demoralized teams on defense and dominated them on offense, too, with a vaunted wishbone offense.

Gary Thomas, only a junior, rushed for more than 1,700 yards and Jeff Slone surpassed 1,000 yards. Jay Shippey and Jim Johnson shared fullback duties, Anderson was the quarterback and Greg Jackson split time in the backfield, overcoming a broken foot that cost him a few games.

Sang was a top athlete as a tight end, return man and punter and the offensive line was ferocious with Terry Bell leading the way. He was voted as the Best Offensive Lineman in Kentucky. Bell was joined on the line by center Terry Lewis, guard Yancey Ramey and tackles Casey Jones and Raymond Hicks.

Shippey and Johnson were punishing runners and Thomas, Slone and Jackson ran like gazelles. Conley said his halfbacks were some of the best blockers he had during his coaching career. Split end Dougie Paige, all 115 pounds of him, could put players twice his size on the ground in downfield blocking. Keith Hillman, a speedy receiver, also played some at split end.

A trip to the movies just what was needed

Ashland had no losses during the regular season, but the team escaped one Friday night against Huntington High, winning 12-6 despite losing three fumbles to improve to 6-0. The players knew it was not their best effort and dreaded practice the following Monday.

Conley said he sensed something was wrong and that the team was playing tired. He told the coaches that instead of a brutal practice, he was taking the players to the movie on Monday to watch “the Towering Inferno,” starring O.J. Simpson, at Midtown Cinema. The players were stunned when they arrived ready for practice and were told to keep their street clothes on and get on the bus. Conley had instructed Hank Hillman of the Boosters Club to reserve the theater – complete with drinks and popcorn – for the team.

It was just what they needed. They came back fresh the next Friday, hammering a good Belfry team 47-7. The fire was reignited.

Ashland closed the regular season at 11-0 with a 43-0 victory over rival Boyd County that wrapped up the district and put them in the postseason. Back then, only district champions advanced to the playoffs. Boyd County had won the previous two seasons against the Tomcats and wanted to spoil their undefeated season. But the Lions were no match for them in at the time was the most lopsided loss in the series.

The playoffs beckon and a flight to remember

Even though the Tomcats were ranked No. 1 and undefeated, their first playoff game was on the road at Dixie Heights in one of the coldest games anybody can remember. After a sluggish first half, a halftime butt-chewing from their head coach got everybody’s attention and Ashland won 36-6. He had captains Sang, Bell and Anderson stand in front of mirrors in the locker room and told them to look into the mirror and ask themselves if they gave their best effort. The rest of the team was watching, and they got the message.

Years later, Sang confessed that he thought he had given his best effort but stared into the mirror anyway. Coach Conley called Sang into his class on the following Monday and told him, “Hey Rick, we watched the film, and you really didn’t play that bad.”

They followed that with a win over Lafayette, 21-6, at Putnam Stadium to advance to the Class AAAA State At-Large championship in Paducah.

The Tomcats were in for a long trip on the other side of the state. But before the Lafayette game was even finished, plans were made to fly to Paducah and the Tomcats became the first team in Kentucky high school history to charter a flight to a game. Ashland was an eight-hour bus ride from Paducah but only a short flight. The Boosters Club raised the money, and the team flew on the day of the game.

Many of the players were making their first plane flight and it was a quiet trip with nobody saying anything. It was only five years since the horrific Marshall University plane crash,

The flight kept their legs fresh for Paducah and Thomas broke a 7-7 deadlock with a 75-yard touchdown run with three minutes to play that gave the Tomcats a 13-7 victory and a spot in the overall state championship game against Jefferson County champion St. Xavier.

St. Xavier was undefeated and loaded with talent. The Tigers had 11 different players on offense and defense and that depth wore down the Tomcats, who lost 20-0 after a tight first half, trailing only 6-0 with Ashland missing at least two good scoring opportunities. It would be the only loss in a 14-1 season, but the 1975 Tomcats have remained one of the most beloved teams in Ashland history.

On Oct. 3, the Tomcats 1975 JAWS team will be recognized at Clark’s Pump-N-Shop Putnam Stadium on their 50th anniversary.