The toughest job in the 16th Region this season had nothing to do with coaching, handling the basketball or knocking down shots from beyond the arc.

It had everything to do with following a familiar voice—one that had become iconic.

Tyler Rowland stepped into the enormous shoes of the late, great Dicky Martin. When Dicky passed away toward the end of the high school football season, the question of who could follow him wasn’t really meant to be answered.

Who could replace him?

The answer then—and now—is nobody.

Dicky Martin was an original. One of one. A voice so memorable that replays of his calls still circulate on Facebook, and people still stop to listen. He is missed, without question, and things simply aren’t the same.

But the man who stepped into his place has done a remarkable job.

Tyler Rowland isn’t Dicky Martin—and expecting him to be would be unfair to anyone. What Tyler has done, though, is begin to grow comfortable in a seat Dicky occupied for more than 50 years of Tomcat sports. Dicky was loud, proud, and unmistakable—a voice even rival fans couldn’t help but hear night after night. He was must-listen radio.

Times have changed, even during Dicky’s era. High school sports once lived exclusively on the radio. Now, fans can watch games from their living rooms through streaming services like My Town TV and Kool Hits. I’m thankful for both. Watching is fun, though I hope radio never disappears. There’s a charm to it that pulls you back in time.

This region has produced a Hall of Fame list of broadcasters—so many that naming them risks leaving someone out. Tyler Rowland has the potential to belong in that conversation.

For Ashland fans especially, radio remains a lifeline. Whether it’s listening live during a game or tuning in afterward for Ryan Bonner’s postgame analysis with Tyler, people are still listening. And if you’ve tuned in, what you’ve heard is a polished broadcaster who improves with every call.

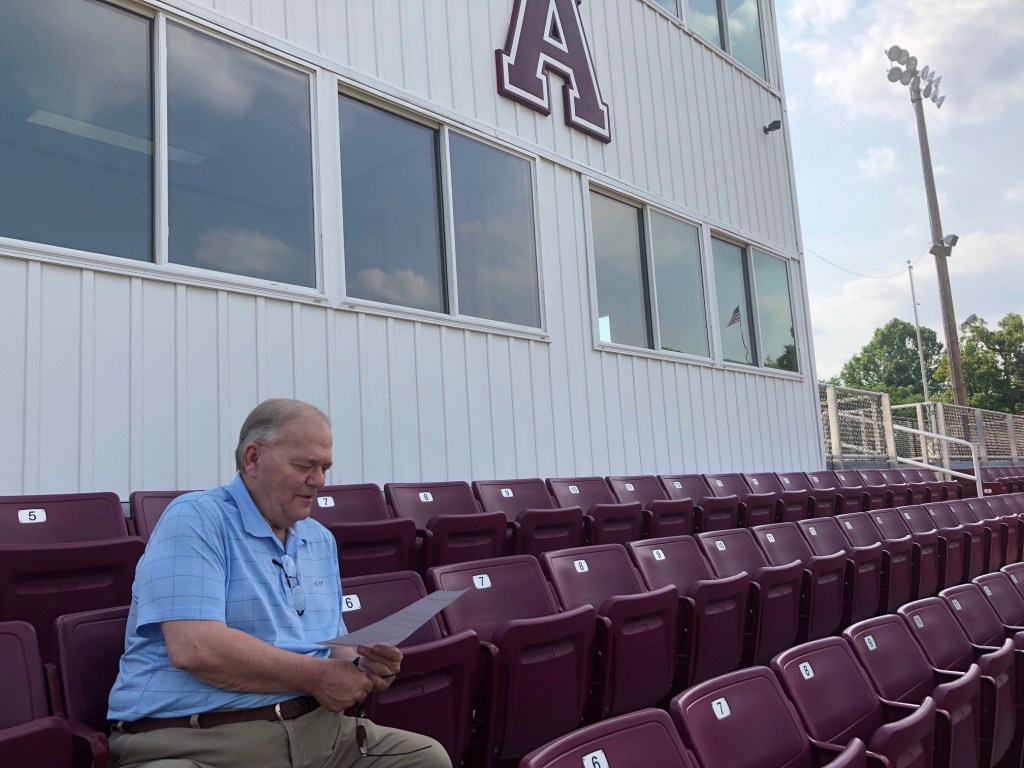

Tyler considers himself a disciple of Dicky, and it shows—especially in his preparation. An accountant by day, his command of numbers is impressive. He’s a savant with statistics. While he has years of broadcasting experience, including time with My Town TV, radio is a different animal. Early on, Tyler was known for his loud excitement on TV. As his voice has matured, it’s grown softer—but also stronger—on the radio.

Tomcat radio is unlike most broadcasts. The tradition built by the Martin family—Dicky and his father, Dick—set the standard for 75 years. Imagine being the person tasked with replacing that kind of history.

It’s overwhelming. But Tyler never let it swallow him, largely because of how much he admired the man who came before him.

The advice he heard most was simple: Don’t try to be Dicky. Be Tyler.

That’s exactly what he’s done. And by doing so, he’s validated the decision made by Tomcat athletic director Jim Conway to hand him the microphone. Tyler’s play-by-play is descriptive, his knowledge sound. You always know the score, the time on the clock, and how far that corner jumper really was. He paints a clear picture without being overly excitable. His strong vocabulary and statistical awareness make his calls both informative and entertaining.

I’ve listened to several of his broadcasts and come away impressed every time. Even when things aren’t going Ashland’s way, he doesn’t rush to blame officials. You might hear, “I’m not sure about that one,” and then he moves on. It’s professional broadcasting—with just the right tint of maroon.

I listened to his call of the most recent Ashland–Boyd County game, a high-scoring Tomcat win. I watched on YouTube while listening to Tyler’s call—barely a second of delay—and he didn’t miss a thing. What he described matched exactly what I was seeing. It was impressive.

If you haven’t listened to this young man yet, give him a chance.

Replacing Dicky Martin was a mission impossible. Everyone knew nobody could truly do it.

But Tyler Rowland is the next man up—and he is the right man to handle the toughest job in the 16th Region, and maybe in the entire state of Kentucky.

And I know this much: Dicky would approve of the job that Tyler has done.